1/1

Played: June 8, 2020

Tuesday, February 13, 1973. A drizzly day in the Bay Area. Archibald “Archie” Ransom commutes to Lawrence Livermore Laboratory in his Dodge station wagon listening to some beautiful music. During the news break, he hears a story about a terrorist bombing at the Transamerica Pyramid the night before. Though it is a headline-level story, the details are sketchy — hardly more than what Archie picked up when he flipped through the newspaper that morning. The radio man reports that someone set off multiple explosive charges along the ground-floor columns outside of the building. Damage was minimal and the structure of the skyscraper is not compromised. No one has claimed responsibility yet. Police are investigating along with the FBI. The city is slightly on edge, though that’s nothing new. There has been a tension in the air the past few years, the result of near-constant stories about insurgent political violence, cult activity, and an epidemic of “sequential” killings by what are assumed to be deranged sex criminals (among them the so-called “Zodiac Killer,” still uncaught). The newscaster switches over to the local weather.

Archie arrives at Livermore and heads down to the Operation URIEL offices in the basement of Building 451. There he is greeted by Sophie Edelstein, URIEL’s chief researcher and “librarian,” as well as another young-looking woman, conservatively but fashionably attired. She introduces herself as Jocasta Menos. Ah, right, Archie thinks — URIEL’s newest full-time member, recently assigned by Granite Peak. Archie assumes Jocasta’s role will be to assist them with URIEL’s other latest acquisition: four monochrome ARPANET terminals that SANDMAN installed onsite a few months prior. In any event, Archie and Sophie give Jocasta the tour, pointing out her cubicle and the coffee maker, the Telex machines (one of which is connected directly to the Peak), the library with its endless shelves of trade magazines, newspapers, academic journals, etc., the classified archives inside a glass enclosure, and Archie’s office (“The door’s always open!” he chummily remarks) with its secure line to Dr. Frank Stanton in New York City. Dr. Stanton is URIEL’s “overseer,” for lack of a better word — a bigwig in SANDMAN, just as he’s a bigwig (indeed, one of the biggest wigs) in the American media-industrial complex.

During the tour, another of URIEL’s members arrive: Mitchell Jefferson Hort. Mitch, though ostensibly a “night guard” at Livermore, is a nondescript post-hippie type, someone Jocasta might expect to see playing back-up guitar with a joint in his mouth. He greets Jocasta with a noncommittal “hey.” Jocasta is polite and deferential despite the vibe she picks up from Archie and Mitch, which is that having “another woman” around office will be a good thing, as now they’ll have someone else to make the coffee, collect the mail, work the Telex machine, etc. Once the tour and the initial introductions are complete, Jocasta takes her place in her new cubicle and starts to review the various three-ring binders full of local procedures and case histories from URIEL’s prior work. She gets the sense this is a pretty disorganized operation. Eccentric, even.

That afternoon, the mail boy arrives with URIEL’s deliverables, several newspapers and magazines among other things. Sophie sets about parsing through everything. She makes a topical index of each item, clips out important or unusual seeming items, and carefully catalogues the rest. Eventually she reaches the San Francisco Examiner. After she flips through the first few pages, Jocasta and Archie notice her go for her phone. She makes a quick call, hangs up, folds the paper carefully and heads into Archie’s office. To Jocasta’s eye, she looks urgent and harried. Sophie tells Archie she thinks he should call everyone into a meeting because someone has written a letter to the Examiner — which the Examiner published — claiming responsibility for the Transamerica bombing. That letter, she says, contains a glyph. Archie can tell there’s a tension, a nervousness, to Sophie’s voice as she explains the situation. Archie takes the paper from Sophie and Sophie continues: “It’s — it’s not functional, Mr. Ransom. Something was wrong with the reproduction. I was not affected by it, but it is absolutely a glyph.”

Archie reads the letter and the article accompanying it. The article reports that the Examiner was asked to reproduce the letter in its entirety. Given the circumstances, and given further the situation with the Zodiac killings several years ago, the Examiner’s editorial board decided it best to publish the letter. Of course, they have contacted the police and the FBI, who believe the letter to be authentic because it contains details known only to the culprit and the authorities. Archie brings in Mitch and Jocasta, and shows them the letter. The glyph embedded at the top does make their heads swim somewhat, despite its flawed transcription. They determine that the glyph is of the SHEG type. In its original form — that is, the glyph viewed by the letter’s recipient — it would have compelled the viewer to OBEY the next command they see or hear. Hence its placement at the top of the letter, followed by the sentence, “Publish this exactly.” Archie folds the top of the newspaper to conceal the glyph, and Jo and Mitch read the rest. Sophie heads to the phones to get ahold of Roger Martin and Marshall Redgrave, URIEL’s remaining members.

At a local bar in Oakland, Roger hears his name shouted out by the bartender Joey. “Say, Roger — you got a call. Sounds like a foreign chick.” Roger puts down his pool cue and walks over. “Yeah. I know this one. Thanks.” Meanwhile, in the rolling hills of Sonoma, Marshall meditates in an outdoor Greco-Roman rotunda. His assistant, Sunshine, brings out a white antique telephone on a silver platter. “The phone, Doc.” Marshall lifts the receiver. “Yes?” Between the two, Sophie conveys the situation: they are needed at Livermore ASAP due to possible Red King exposure in the print media. Roger asks if it’s worth a speeding ticket to get there; Sophie says cruising speed with the possibility of a ticket may be warranted. Roger settles up at the bar, gets in his car, and heads off. Marshall hangs up without saying a word and tells Sunshine to get his driver.

While the rest of URIEL waits for Roger and Marshall to arrive, Jocasta suggests that this must have been “some kind of inside job” because the “reason that they printed this so hastily is because whoever saw it first was affected by the original glyph. That means it had to be somebody in a position to make editorial decisions.” Mitch disagrees:

Mitch: No, no, I mean, if you open up an envelope and it's got the glyph in it, it says publish this exactly, and it's not your job to decide what gets published, you're going to immediately take it to somebody who does have that power and be like, look at this it needs to get published and they'll see it and they’ll be like, oh yeah, obviously. So I don’t think that’s necessarily —

Jocasta: Fair.

Mitch: — doesn’t necessarily mean that it didn’t come through normal channels to the newspaper.

Mitch further suggests that the letter-writer seems to be establishing a dichotomy between ziggurats and pyramids. Ziggurats represent History B. Pyramids represent History A. The latter sort of “paper over the holes” in reality. Jocasta notes that the letter bears a striking similarity to the Zodiac letters from the late ‘60s. “I would almost assume it was a forgery or a copycat, maybe, if it wasn't for the presence of that glyph. Did anybody run prints on the envelope or the letter?” Sophie says no, not yet — to do that, they’d need to reach out to their contacts at the SFPD or the FBI. Mitch says either way, step one seems to be that they should confiscate the original letter. “That’s something we do, right? That’s like, the thing we do?” As he says this, Roger and Marshall arrive and take their seats at the conference table. Archie shows them the letter, taking care to conceal the glyph, and Sophie catches them up on the situation.

The team discusses what they know and what they can surmise. Jocasta volunteers that, from a strictly “vanilla” occult perspective, the letter seems like something a bog-standard conspiracy-obsessed person might write. It is only the half-veiled allusions to History B symbology that sets this apart from the boilerplate weirdo demand letter. Archie traces out some memetic and esmological equations on a legal notepad, attempting to discern what the “downstream” impact of this letter will be on the paper-reading public. He also wonders aloud what resources URIEL can bring to bear to intervene at the Examiner in order to stop the letter from getting re-printed in the evening edition, and to obtain a copy of the original letter, assuming it is still at the newspaper’s HQ. After a moment or two of analysis, he concludes that there is no back-masking subliminals or secret cyphers in the printed version of the letter. The writer is obviously pretty educated, making the references he does, and he seems familiar with certain left-wing concepts, but does not seem to evince any particular left-wing beliefs.

Marshall, staring at the ceiling, muses that this does not seem like a five-alarm fire situation — he’s intrigued, but not especially concerned. That said, from a strictly psychological perspective, he believes the writer acted alone and that, by not signing the letter, is likely unconcerned with notions of fame or notoriety. As far as ‘70s fringe actors go, that’s a bit unusual. He also thinks the letter writer is a probably a white male, in his 20s or 30s, reasonably well educated. But for the History B elements of the letter, he’d posit that the writer is schizophrenic, as evidenced by the fact that there’s no demand. Roger jumps in:

Yeah, I want to talk about that because that's the part — that's the creepy shit. There's going to be some children in the ground and people are going to be — if that gets published in the paper, do you know how people are going to freak out? You know it's going to be the parents; they're the ones that freak out that someone's following their kids and watching them read their ABCs and then wants to put them in the ground. I think there's sort of a panic situation you might want to think about here gentlemen. I mean — uh, gentlemen and lady, I should say. Finally, um, there's a little bit more here to also deal with in terms of, are some kids gonna die?

Jocasta again notes the parallels with the Zodiac Killer, who also threatened to “pick off” children as they came home from school and, on another occasion, threatened to hijack a school bus full of kids and bury it underground. Marshall says these parallels may be intentional: the writer could be deliberately seeking to emulate the Zodiac in order to throw people off his scent. But he does not believe that is likely. From the rest of the letter, it seems his threats are sincere. This jives with Archie’s understanding of History B. He explains that blood and death is one of the most “common” methods of bringing History B to the fore. Something about human sacrifice seems to pierce the ontological framework of History A, providing either an opening for History B corruption or allowing for full blown irruptions. Mitch says:

I think that if — for a lot of people — if you were going to pick a site to have a massacre, like a school would probably not be the first choice, right? A lot of people would think hospital, right? Or like, crowded apartment building or tenement or something like that. But school specifically … I like the idea that, um, this is somebody who has some kind of connection to children or schools, pre-existing. It just seems like a little bit of a leap to me. I dunno. I could be off base there.

He sips his coffee. Along these lines, Sophie notes that the bombing at the Transamerica Pyramid did not involve any casualties or even injuries. Even the structure itself was barely damaged. That seems incongruent with the demeanor of someone who is primed to kill a bus-load of children. Archie notes that the bombing is another lead in need of investigation. Mitch says that blowing up a building is harder in real life than it looks on TV, so just because the Pyramid didn’t collapse doesn’t mean the bomber didn’t mean for it to collapse. Jocasta says that, tactically speaking, a good order of action items would be (1) get someone to the Transamerica Pyramid to investigate the site, and potentially to get inside; (2) get to the Examiner to talk with whoever received the letter and caused it to be published; and (3) reach out to law enforcement to see what they know about the situation. Sophie writes all that up on the chalkboard.

The team decides who will tackle what. Roger volunteers to take (1), since he has demo experience and an FBI badge that’ll get him past the perimeter around the Pyramid. He can also use that cover to obtain the blueprints of the Pyramid that are presumably on file with the city. Jocasta takes on the job of contacting the FBI team assigned to this case, since she can use her cover in Army Intelligence to explain her involvement. Archie and Marshall elect to go to the Examiner and do damage control there. Mitch says he’s going to go check out some schools, see what he can see. Since he doesn’t have a car, he’ll take a cab. So decided, the team disbands.

Roger hops in his car and makes haste into town. His first stop is San Francisco’s municipal records department, where he uses his law enforcement cover to obtain copies of the Transamerica blueprints and permitting papers on file with the city. Collating those records with what he read in the paper about the explosion, he soon determines that whatever devices the bomber set off were pretty week. There were only a couple of charges placed on a few of the exterior columns; those charges did only superficial damage. Plus, the tower was designed with the most up-to-date earthquake resistance engineering. It would take a truck full of fertilizer, perhaps more than one, to bring the thing down. Roger thinks: this dude was either incredibly incompetent or did not really intend on damaging the building in a meaningful way. Anyway, he has some copies made and then hops back in his car to travel to the bombing site.

The Pyramid is surrounded by a fairly extensive police cordon. From a quick drive-by, he notes that all the scorch-marks from the bombing are located on the exterior columns or “struts” that face an adjacent park containing a number of newly-planted redwood trees. The scorch-marks are themselves located about 15 feet up from the base of the columns, each forming something akin to an “eye in the pyramid” symbol using the columns’ natural triangular orientation. Roger parks, slaps on his FBI badge, and heads to the cordon, where he introduces himself as an agent sent from “out of town.” The local cops wave him through. Examining the scene, and questioning some of the officers on site, Roger learns that the explosives were likely made from plastic. There was a single night watchman working that night, and he did not report observing anyone scuttle up the columns to plant the bombs (which means he’s either the least observant watchman in history or something fishy was going on). When the explosives went off, he was inside the building and felt the “quake” they caused. But nobody saw nothin’, otherwise.

Jocasta strides into the FBI’s San Francisco field office. She introduces herself as agent with Army Intelligence and that she has been sent here to eliminate a potential Army suspect. With the right credentials, this gets her access to the evidence locker, where the two agents assigned to the — Tom Padden and Monte Hall — show her the original letter and some samples taken from the scene of the explosion. Being careful to avoid looking at the glyph, Jocasta finds that the original letter is handwritten in black ballpoint ink. The exterior envelope is postmarked from Pittsburg, California, a small fishing town in the North Bay. The final piece of evidence they show her is a handwritten “confession” on the back of a narrow strip of paper. The confession, written in the same handwriting as the letter to the Examiner, states that the bomber used six hand-shaped C4 explosives, placed at such-and-such height on X, Y, and Z columns — information only the culprit would know. Flipping the paper over, Jocasta sees that it’s a comic strip. A Steve Canyon comic strip.

As soon as she glimpses the first panel of the comic, Jocasta is overwhelmed with impressions from another person’s mind — indeed, the man who wrote the confessions and planted the bombs. The single emotion she pulls from this experience are intense waves of anger. She “watches” as the man (she’s pretty sure it’s a man) writes something on the back of the strip, flips it over to look at the comic, gets angrier, and then flips it over again to resume writing. One of other things she is able to observe, on the table in front of the man, is the comic book that this strip was clipped out of: a 1960s issue of Stars & Stripes. This vision pierces Jocasta’s psyche, shaking her up considerably. She collapses into a nearby chair.

As they drive to the Examiner’s offices, Marshall re-reads the letter with an eye toward sussing out any untrue statements or insincerities the writer may have harbored. From his earlier assessment and from the re-read, he deduces that the writer is perhaps not wholly on the side of the Red Kings. He is manifesting a good deal of enthusiasm for their cause, but almost in a “doth protest too much” fashion. Still, he seems sincere in his intentions, including the thing with the kids.

Marshall pitches his idea to Archie about their cover: they’re doing a favor for a famous actress — Archie due to his connections in the media and his long career in PR, and Marshall as the actress’ guru and “life coach” — who misplaced a copy of a script she’s involved with. The script contained the letter, and she was horrified to find it in the paper, because the whole project is under embargo. They’re not going through “official channels,” that is, the studio, because that would require the actress to divulge that she was the one who lost the script. She’s hoping that Archie and Marshall can fix the fuck-up without anyone catching wise.

Archie: That seems like an awful long way, a long way around Marshall. I mean, you know, I'm not entirely comfortable with that deception. Can't we just — can't we just level with them? Tell them these are the ravings of a maladjusted mind and appeal to their better nature? They don't want to be putting this poison out there into people's heads. This is going to scare people.

Marshall: I hear you, man. I hear you. But in my experience when you're dealing with the press, it's generally better to come at it from a liability angle as opposed to a moral virtue angle. And, you know, deception? Would we use the word deception? We do have a client. They shouldn't be reading this stuff. It is under embargo, in a sense. So, you know, we're just putting it in a context that these people will be able to understand.

Archie acquiesces and they go over their cover one more time before arriving. Inside, they fast talk their way past the reception desk and to the newsroom. After about 10 minutes of waiting, they are ushered into the editorial suite of the Examiner. The entire editorial board is assembled. Among them is Ed Dooley, the Examiner’s news editor for the past 20 years; Thomas Eastham, the paper’s executive editor; and (of course) Randolph Hearst, the heir to the Hearst fortune and the paper’s owner. After a round of handshakes, Eastham says he and his team understand that they, Marshall and Archie, have some information about the letter. Archie clears his throat and explains the cover story. “This is all a terrible mess,” he confides, “and the first thing I want to say is that, you know, is just that we’re so glad — so thankful that nobody was hurt. That’s really important. But there's been some kind of a crazy mix-up, and I don't know exactly how you got ahold of it, but the letter's not real. It’s show business. It’s from a project that a client of mine is working on and that Dr. Redgrave is involved with. And, I mean — you’ve all read the letter, you must understand it’s all nonsense. But we don't want to disturb people. We don't want to distress people. Ultimately there must be some sort of mix up because it's tied to this show business project.” As he explains a bit more of the details of the situation, Archie emphasizes in this is all going to make the newspaper look quite silly once the truth comes out, and implies that the board may face liability if this isn’t cleaned up quickly.

As Archie talks, Marshall surveys the room. He notes puzzled looks on the faces of most of the editorial board, though a few seem confused about why the FBI is involved if the letter is a hoax. Most notably, though, Marshall spots Dooley sort of staring off into the middle distance. He quickly deduces that Dooley probably opened the letter in the first place, took the glyph head-on, and ordered its publication. Armed with this intel, he relocates to another chair across from Dooley and asks how long he’s been with the paper. The room goes quiet.

Ed: Going on two decades.

Marshall: You were around for the Zodiac letters?

Ed: Yes. Yes, I was.

Marshall: And those were crazy. Those were crazy times. I think we can all agree.

Ed: I think we exercised our best judgment back then.

Marshall: Yeah, yeah. Yeah. So if — so how familiar are you with Zodiac letters? You know, the ones that were sent into the papers and at the FBI confiscated?

Ed: About as well as anyone at this table. And over at the Chronicle, I think. I think we're all very familiar with them. They shocked us.

Marshall: OK. And, you know, I have a copy of this letter that you guys published with me. I’m just gonna lay it out on the table here. Do you notice any similarities between this letter any of the Zodiac letters back when you were working?

Ed: Well, there is the mention of the school bus …

Archie catches on to what Marshall is up to. He resumes talking with the rest of the board, addressing their questions about the FBI’s involvement and how this is all, really, just a big misunderstanding. They’re hoping to save the Examiner some real embarrassment by approaching them in this way. He casually invokes words like “copyright” and “due diligence” and “the studio” and gradually brings them over to his side. Marshall, simultaneously, lulls Dooley into a suggestible hypnotic state, helping Dooley connect the dots that this letter is merely part of a movie in the works about the Zodiac killings. The fact that he published it without any oversight from the board, and knowing the similarities between the “bomber’s letter” and the legit Zodiac letters, calls into question his professional judgment, doesn’t it? The shot lands. Ed gets a little choked up and excuses himself from the room. Marshall follows.

Mitch sits in the back of a cab. He makes conversation with his driver, whom he periodically instructs to take a random turn, head down a specific street, make his way to a particular landmark. The driver figures he must be a sightseer. After a while, Mitch finds himself sitting in traffic in front of the Transamerica Pyramid. As he glances out the window, he spots a black-and-white Newfoundland dog and a smaller terrier nosing around some bushes out in front of the Pyramid. This is strange; there are not a lot of stray dogs in downtown San Francisco. Mitch tells the cab driver this is where he gets out. He pays the man and jumps out of the car, heading in the direction of the dogs. When he gets to them, he gets down his knees, greeting them in a friendly tone, and asks if he can pet them. He sees that they don’t have collars or leashes, no identification of any kind. The bigger of the two — the Newfoundland — is especially friendly, and saddles up to Mitch. Mitch spots that his muzzle and front paws are caked in a dried dark substance. Looking closer, Mitch determines it to be blood. He inspects the terrier and finds the same: blood on his snout and paws. After patting them for a moment, the two turn and trot further into the park. Mitch pursues. He loses sight of them for a moment as they turn a corner, and as he does, he senses History B contamination nearby. He looks around.

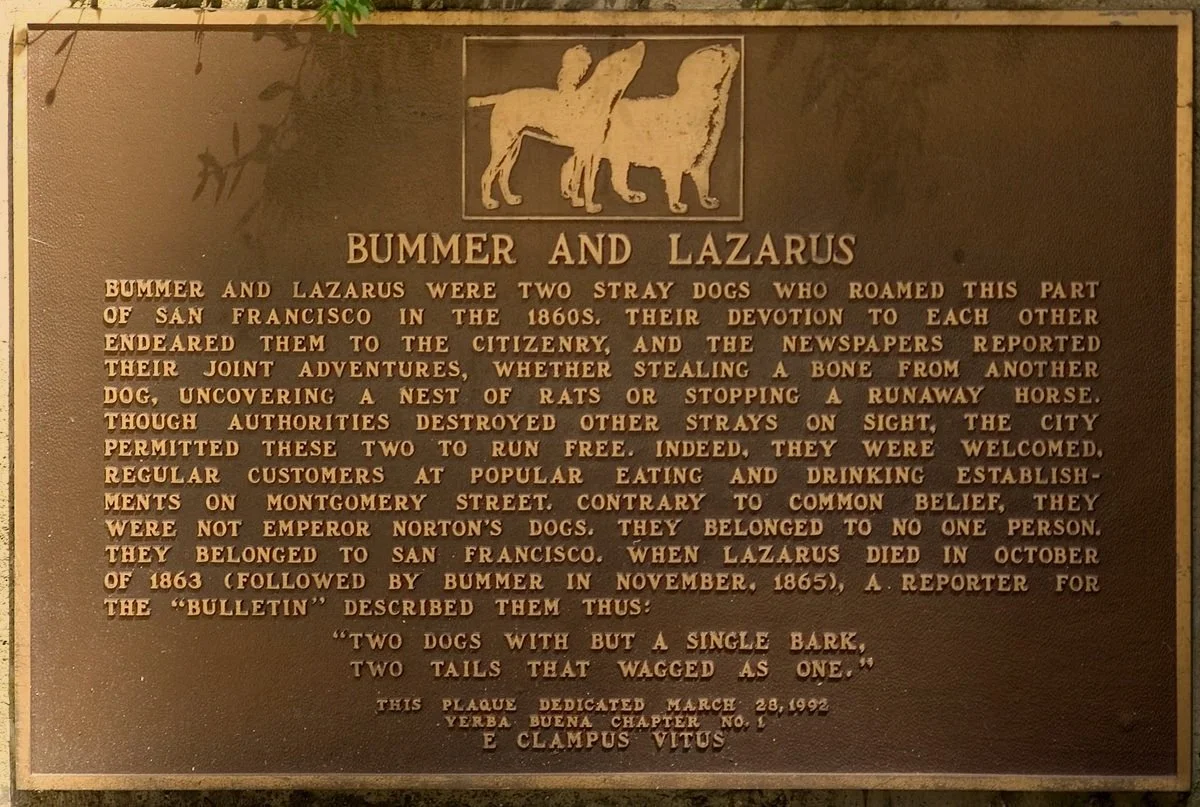

Roger emerges from behind one of the security cordon’s view-blocking panels and sees Mitch staring at something. How Mitch got through the perimeter is beyond Roger, but then again, that’s kind of how Mitch operates. Mitch, meanwhile, follows his instincts in the direction of the History B contamination, eventually stumbling upon a plaque attached to a rock. The plaque depicts two dogs with the words “Bummer and Lazarus” underneath. The plaque is dated March 28, 1992. As Roger watches, Mitch pulls out his camera and takes a photo — but he’s not sure of what, because he doesn’t see anything there. He can’t be sure, but it looks like Mitch is sweating a bit. More than a bit, in fact.

At the FBI office, Jocasta holds her head in her hands as she experiences … someone else’s memories of … Vietnam? She is a pilot. She is in a really rickety plane flying over a jungle. Everything is reverberating and rattling around her. She can hear voices coming over the radio. Suddenly, she spots a small village on a river. There’s a Viet Cong flag flying atop one of the huts. She says something into a radio and then pulls a trigger. White phosphorous drops from the belly of her plane onto the village below. She thinks she can hear screaming, but no, that can’t be right — no one could hear anything over the noise of the plane. Then, a voice in the back of her mind. It says: “The next time that you do this, you will be ours.” With that, her mind clears and she snaps back to reality. Padden and Hall ask if she’s alright, and she says yes, just a flash of a headache. She’s been deeply involved in this case from the beginning and it’s lead her to some dark places. She offers them her business card and asks them to keep her informed about any further developments. She then attempts to gather up the evidence as if she’s going to leave with it. They don’t move to stop her. She makes her way to the exit.

Returning to the Examiner, Archie keeps working on the board, helping them strategize how best to clean up this “mess.” As he’s doing so, a man in a priest’s cassock pops his head into the conference room. “You guys talkin’ about the letter?” he asks. Snap to Marshall in Dooley’s cubicle. Dooley beseeches Marshall to understand that he had no choice in publishing the letter — he saw it, and he knew what he needed to do. Marshall nods understandingly and ushers Dooley into a quiet conference room. There, he hypnotizes Dooley into recalling everything he can about the letter: who it was addressed to, when he received it, the handwriting, the post-date, etc. Dooley recounts all that he knows, including that the letter was addressed to him, specifically, and included a comic strip. His memory is that it was postmarked from Pittsburg, California. But the thing that most stood out to him was the glyph. The glyph got into his very soul, it compelled him to believe that publishing this letter was of the utmost importance. So important, in fact, that he did not clear it by his board and just directed its publication personally. Marshall debates, internally, how best to brainwash Dooley of this information.

At the Transamerica park, Roger approaches Mitch. It gets hotter and hotter as he does, like he’s approaching a sunlamp. Mitch wipes some sweat from his brow, mumbling to himself about how “there was blood, there was blood.” Roger asks if Mitch is OK and Mitch points down at the ground. Roger looks and sees … a wall. Nothing else. No plaque. Mitch, looking again, sees the plaque is gone. “Damn it,” he mutters.